Critique: Think fast: a tensor streaming processor (TSP) for accelerating deep learning workloads

Paper: Abts, Dennis, et al. “Think fast: a tensor streaming processor (TSP) for accelerating deep learning workloads.” 2020 ACM/IEEE 47th Annual International Symposium on Computer Architecture (ISCA). IEEE, 2020.

Summary

This work introduces a novel processor architecture called Tensor Streaming Processor (TSP) which utilizes the property of abundant data parallelism in machine learning workloads and the advantages of the producer-consumer stream programming model in terms of performance and power efficiency. From my point of view, I think that the designed architecture is sophisticated due to its consideration in the trade-offs for workloads and power envelope. Strictly speaking, there is room for improvement in the experimental part. Moreover, it should be noted that what is different from other papers is its section organization. In this paper, it adopts an engineering and empirical structure to describe the whole story.

The work is conducted by a famous and emerging artificial intelligence company called Groq, Inc . Their proposed TSP has gained a significant influence and profit in the market as well. Hence, For more fairness and rationality, the way of this critique is slightly distinguishable from the previous. In the following parts, I will analyze the paper in detail at the aspects of clarity, novelty, technical correctness with reproducibility, etc. independently rather than ambiguous and general strengths or weaknesses.

Clarity

The paper is clear enough but could benefit from some revision. As I mentioned above, its section organization is different from other papers.

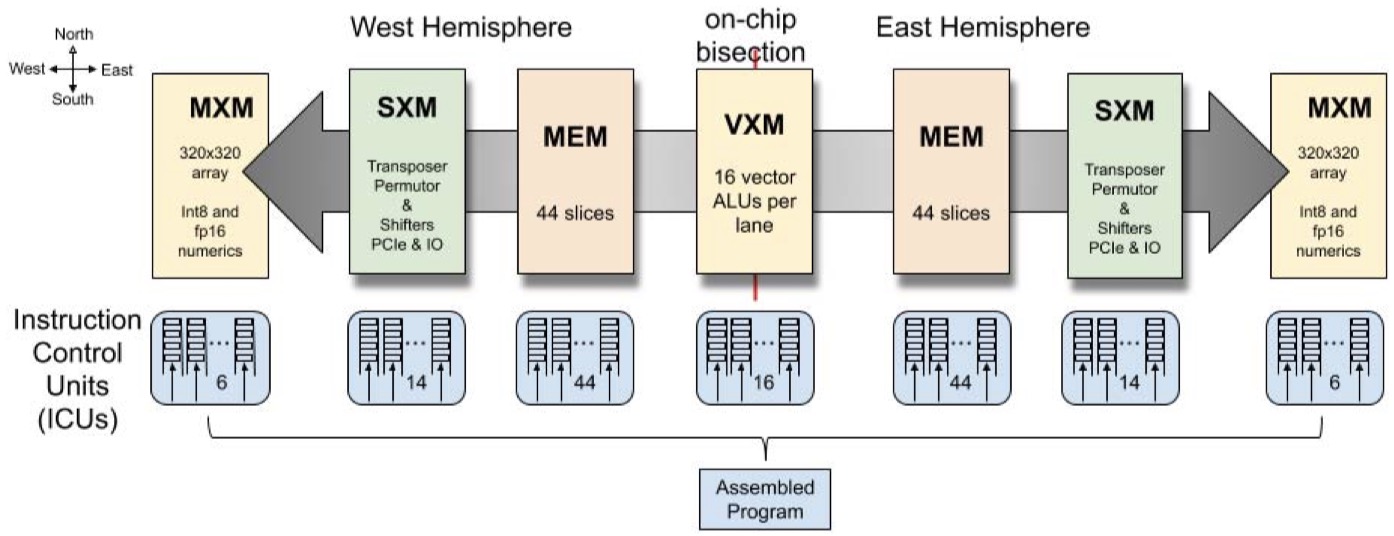

Specifically, the work starts with the introduction for functional-sliced tile microarchitecture and the stream programming abstraction built upon it in SECTION.I. Then, the authors describe their first implementation of the TSP in 14nm ASIC technology, memory system, and functional units, programming model, instruction set architecture (ISA), and design tradeoffs for efficient operation at batch-size of 1 in SECTION.II traditionally. Afterward, the contents in SECTION.III are about the instruction set where the paper shows the instruction control unit, memory, vector processor, matrix execution module, and switch execution module. Definitely, this part should belong to the methodology. I take it for granted that authors have considered the complexity of architecture design. This is why the authors separate these methods empirically which lacks compactness to a certain degree.

The confusing thing is coming, the title of SECTION.IV is ResNet50 [1]. ResNet50 is a popular image classification model published in CVPR in 2016. All experimental results including operating regimes, matrix operations, and on-chip network in SECTION.V are based on it. The authors spent a lot of space to introduce ResNetT50 as an example in terms of resource bottlenecks and quantization with TSP. At the end of the experiment parts, SECTION.V provides initial proof-points and performance results of mapping the ResNet50 v2 image classification model to their underlying tensor streaming processor. Additionally, the technical correctness and reproducibility in these sections will be discussed later in the critique.

Thus, I think the methodology and experimental parts can be re-organized furtherly. For example, SECTION.III (INSTRUCTION SET) can be merged with SECTION.II (ARCHITECTURE OVERVIEW) which leads to a new section introducing the detailed architecture design with several subsections. Similarly, SECTION.IV (ResNet50) and SECTION.V (DISCUSSION) can also be merged since their contents are all related to the experiments of ResNet50. Of course, these are just my humble opinions and circumstances alter cases.

Novelty

There is no doubt that this article has many innovations. One of the strengths is that in contrast to conventional multicore, where each tile is a heterogeneous collection of functional units but globally homogeneous, the proposed architecture inverts that and it has local functional homogeneity but chip-wide (global) heterogeneity.

To be more specific, in terms of functional slicing in SECTION.I.A and SECTION.II.B, the TSP re-organizes the homogeneous two-dimensional mesh of cores into the functionally sliced microarchitecture. That is to say, each tile implements a specific function and is stacked vertically into a “slice” in the Y-dimension of the 2D on-chip mesh which disaggregates the basic elements of a core. Thus, a sequence of instructions specific to its on-chip role can control each functional slice independently. For instance, the memory slices support Read and Write but not Add or Mul, which are only in vector and matrix execution module slices.

Besides, the proposed TSP exploits the advantages of parallel lanes and streams. The TSP’s programming model is a producer-consumer model where each functional slice acts as a consumer and a producer of one or more streams. In this work (SECTION.I.B), streams are implemented in hardware by a chip-wide streaming register file. They are architecturally visible and transport operands and results between slices. A common software pattern involves reading operand data from one or more memory slices that are then subsequently consumed and operated on by a downstream arithmetic slice. More details can be found in the original paper.

In summary, compared with the complex traditional architecture based on CPU, GPU, and FPGA, the proposed TSP also simplifies the certification deployment of the architecture, enabling customers to implement scalable, efficient systems easily and quickly.

What’s more, from my knowledge scope and some statements in paper [3], a pattern begins to emerge, as most specialized processors rely on a series of sub-processing elements which each contribute to increasing throughput of a larger processor.

Meanwhile, there are plenty of methods to achieve multiply-and-accumulate operations parallelism, one of the most renowned techniques is the systolic array [2] and is utilized by the proposed TSP. It is not a new concept. Systolic architectures were first proposed back in tx tsphe late 1970s [2] and have become widely popularized since powering the hardware DeepMind [4] used for the AlphaGo system to defeat Lee Sedol, the world champion of the board game Go in 2015.

Technical Correctness & Reproducibility

In this part, the experimental parts will be analyzed in detail. As I have mentioned above, the paper implements ResNet50 only. It can be seen in SECTION.IV, the authors define an objective first, which aims at maximizing functional slice utilization and minimizing latency. That is to say, the TSP is supposed to take advantage of streaming operands into the vector and matrix execution modules as much as possible. Then, a detailed resource bottlenecks analysis is given to construct a feasible optimization model. It is worth mentioning that the paper provides readers with quantization and the results of model accuracy in SECTION.D.

The results in this paper are encouraging at first glance and the authors claim a fairly staggering performance increase. However, the primary test case is just ResNet50 which cannot convince readers and users. As far as I’m concerned, the work should demonstrate and compare more applications with deep learning models. Only in this way can we truly accept the model proposed by the paper technically.

From the discussion part in SECTION.V, I find that their initial implementation of ResNet50 was a proof-point and reference model for compiler validation, performing an inference query of the ResNet50 model in < 43μs, yielding a throughput of 20.4K images per second with each image sample being a separate query. In another word, the batch size in this case is 1. Though the work does specifically call this a “Streaming Processor” in the whole story, I’m not sure that using anything besides a batch size of 1 for inference is entirely fair, but perhaps I’m misunderstanding what they mean by streaming.

Furtherly, it is challenging to directly compare a GPU vs an ASIC style chip like this though. I would like to see more detailed performance comparisons vs something like Google’s TPU [5] since GPUs are throughput optimized.

Conclusions

In fact, Groq’s TSP architecture is driven by the widely-applied artificial intelligence, which can achieve computational flexibility and large-scale parallelism without the synchronization overhead of traditional GPU and CPU architecture. This provides an innovative example for the industry undoubtedly. Besides, the proposed TSP can support both traditional machine learning models and new machine learning models. It is also currently running on customer sites for x86 and non-x86 systems. At the same time, because the TSP is designed for applications in related fields such as computer vision and artificial intelligence, it frees up more silicon space dedicated to dynamic instruction execution. Last but not least, in terms of latency and inference performance, the proposed TSP is much faster than any other architecture on most tasks.

Academically, this paper is not satisfactory to some extent due to its unusual paper organization and experimental lack though, it is still an excellent work with significant progress in the industry of AI-based architecture. Therefore, I think, the shortcomings in the paper are trivial.

References

[1] He, Kaiming, et al. “Deep residual learning for image recognition.” Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition. 2016.

[2] H. Kung and C. E. Leiserson, “Systolic Arrays (for VLSI),” in Proceedings of Sparse Matrix, vol. 1. Society for industrial and applied mathematics, 1979, pp. 256–282.

[3] Azghadi, Mostafa Rahimi, et al. “Hardware implementation of deep network accelerators towards healthcare and biomedical applications.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2007.05657 (2020).

[4] Gibney, Elizabeth. “Google AI algorithm masters ancient game of Go.” Nature News 529.7587 (2016): 445.

[5] Jouppi, Norman P., et al. “In-datacenter performance analysis of a tensor processing unit.” Proceedings of the 44th Annual International Symposium on Computer Architecture. 2017.

OmegaXYZ is licensed under a CC BY-SA 4.0 Generic License.